Key Takeaways

Key Takeaways

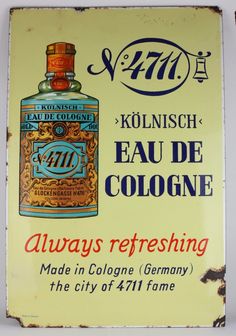

- Cologne invention: Cologne was invented in 1709 by Giovanni Maria Farina in Cologne, Germany. He named his fragrance Eau de Cologne after his adopted hometown.

- Cologne evolution: Cologne evolved from a light and fresh scent made of local herbs and fruits to a generic term for men’s fragrances. It also became associated with healing and hygiene.

- Cologne innovation: Cologne became more sophisticated and diverse with the introduction of alcohol-based fragrances, such as Hungary Water in the 1400s. The first cologne marketed specifically to men was Pour Un Homme in 1934.

- Cologne selection: Cologne should be chosen based on your personality, preferences, and goals. You should test it on your skin before buying it and see how it changes over time.

When Was Cologne Invented?

Cologne was invented in 1709 by Giovanni Maria Farina in – shocker – Cologne, Germany. He was an Italian perfume maker from Santa Maria.

On the brink of his discovery, he wrote a rather excited letter to his brother:

“I have found a fragrance that reminds me of an Italian spring morning, of mountain daffodils and orange blossoms after the rain”.

Giovanni Maria Farina, 1708- Eckstein, Eau de Cologne, p.8

His first efforts contained around 2-5 % alcohol, which is incredibly weak compared to modern standards (80-90%). This means the fragrance won’t have been projecting very far, but hey, it’s a start.

He was working with locally sourced essential oils and herbs, which provided Eau de Cologne with its distinct fresh fragrance.

Eau de Cologne

As homage to his adopted hometown, Farina named the concoction Eau de Cologne – and the rest is history.

His ability to produce a complex, light fragrance composed of other smaller elements was unparalleled at the time. The French parfums available at the time were often overwhelmingly powerful – but Farina had got his blend just right.

People would refer to his creation as the “aqua mirabilis” – or “miracle water” if your Latin is a little rusty. It became a sensation and was delivered to almost all royal houses in Europe.

Eau de Cologne’s success did not go unnoticed. Before long, the market was flooded with businesses looking to imitate Farina with their own colognes.

A single vial of Farina’s blend cost the equivalent of six months’ salary for the average professional. There was always going to be demand for more accessible knock-offs.

Many of these imitations would even copy the “Eau de Cologne” name to achieve sales. That’s how the term “cologne” came to be a catch-all for men’s fragrance.

The original formula is still produced in cologne to this day, in the original factory – now complete with a museum and fragrance shop.

The company has stayed in the family and is currently run by his 8th generation descendants. They protect the exact proportions of the recipe, which remains a highly guarded secret to this day

| Essential Oils | Local Herbs |

|---|---|

| Lemon | Lavender |

| Orange | Thyme |

| Bergamot | Rosemary |

| Neroli | Petitgrain |

| Grapefruit | Jasmine |

Ancient Fragrance

So before Farina came along, people were walking around smelling terrible, presumably?

Well, not exactly. Fragrances still existed, and were popular – but they were less sophisticated – and all unisex.

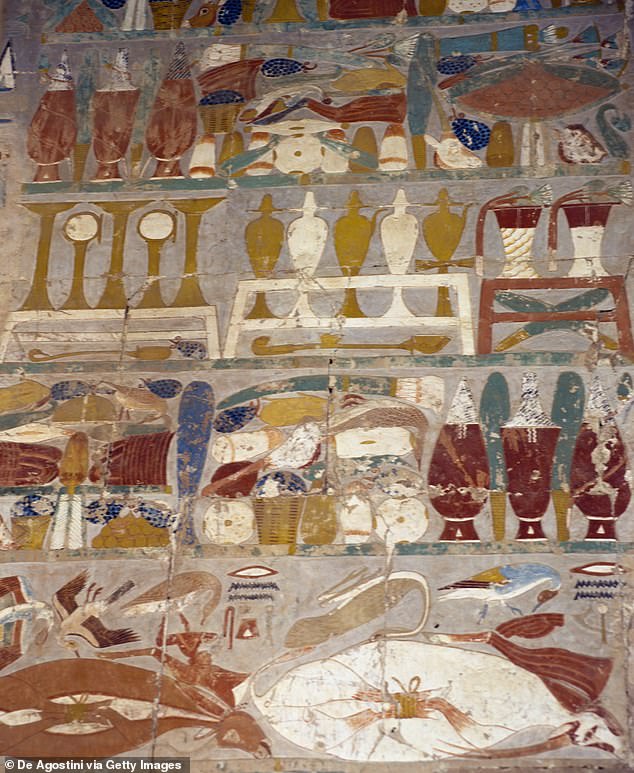

The Egyptians

There’s debate over where perfumery originated. The Mesopotamians had been burning incense for religious ceremonies as early as 4000BC, for instance.

However, the earliest recorded use of anything approaching conventional perfumery was in Egypt, in 2000 BC.

They were the first to concentrate fragrance, extracting natural oils made from flowers, woods, and resins. They’d combine these extracts with animal ingredients like musk and leather to produce scent blends.

Like the Mesopotamians, the Egyptians initially used perfumes exclusively for religious ceremonies. Gradually, these fragrances became more common and affordable.

It became fashionable for Kings and high society to apply these fragrant oils to their skin. The less fortunate had to settle with adding a dash to their bath water and taking lengthy soaks to adopt the fragrance.

Despite the church losing its monopoly on scent, fragrances were still believed to hold holy qualities. The perfume was known as the “sweat of the gods”, and Mummies were buried with a vial of fragrance at their feet.

While we’re on the subject of vials, you can thank the Egyptians for that, too. They invented glass and had the bright idea to store perfumes in glass bottles. Before that, perfume was stored in clunky clay and wooden containers.

Can you imagine what your cologne collection would look like without the Egyptians? Everyone likes a swish-looking bottle.

The Romans

Then, the Romans took perfumery to the next level. I mean, they literally invented the word.

“Perfume” comes from the Latin “per” or “through”, and “fumus”, which means “smoke”.

In an age of incense as one of the primary sources of fragrance, a perfume giving the effect of having been “through – smoke” makes a lot of sense.

Like the Egyptians, the Romans would use fragrances for religious ceremonies. But they‘d also use them as part of relaxing, spa-like treatments for the wealthy at the famous Roman baths.

After their exercise, they would be massaged with scented oils as a means of unwinding and muscle restoration. They’d also smell great afterward, which was a way to remind others of their class and status.

This representation of power was blatant in Roman bottle design. They would often use hollowed-out precious stones or grandiose and complex glassware.

The Romans developed aftershave, too. It was originally intended as an antiseptic to prevent infections resulting from shaving. The Romans were ahead of their time but were still pretty unsanitary compared to modern standards.

At this point, aftershave fragrance was a secondary concern, but the medicinal herbs and spices provided a pleasant scent all the same. As cleanliness standards improved, aftershave became less about staying safe. and more about simply smelling good.

It was big business. In 2004, archaeologists uncovered a Bronze Age Roman industrial district in Cyprus. The site was home to a perfumery, which contained the remnants of 12 separate fragrances, and storage jars of more than 500 liters each.

The scale of the operation suggests that Roman perfumery was serious business, and they’d managed to crack the code of mass production.

The Romans were known to hollow out precious stones or blow magnificent glass to hold their fragrances.

Fragrance in Europe

Hungary Water

Let’s jump ahead to the 1400s. That’s where we find the first “alcohol-based” ie majority alcohol, fragrance, Hungary Water, was produced.

That’s significant because it was a real technological leap forward. To this day, we haven’t been able to find a carrier method for fragrances more effective at maintaining and projecting fragrance than alcohol.

Every cologne you own (except your solid colognes, wiseguy), owes something to Hungary Water. It was created for Queen Elizabeth of *drumroll please* Hungary.

It revolved around a primary note of rosemary and remained one of the most popular scents in Europe right through to the 18th century.

| Alcohols and Essential Oils | Herbs |

|---|---|

| Brandy | Rosemary |

| Wine | Thyme |

| Orange Blossom | Lavender |

| Lemon | Mint |

It was often prescribed as a ”cure-all” to those suffering from anything from toothaches to ringing ears. Some users even believed that it could even help reduce blindness and deafness.

16th Century England

This is where perfume started to become commonplace and permeate society. Queen Elizabeth the 1st, who ruled during the 16th century, absolutely hated bad smells. She made it mandatory for her servants to chew peppermint and thyme, and called for all public places to be manually scented.

Probably a good thing too. Sanitation systems were not what they are today. It must have smelt terrible.

It also became common practice for people to wear fragrances to mask personal body odor. You’d probably have been very grateful if you were around at the time.

The rich would wear legitimate perfumes, but even the lower classes would improvise with assortments of herbs and spices.

Perfume had hit the mainstream.

17th Century France

King Louis XIV took fragrance very seriously. He demanded a new scent for every day of the week! His shirts were infused with fragrances like orange blossom, rose water, musk, and spices.

Well, if you’re the king, you’ve gotta keep things fresh.

Napoleon was the same. A quarterly bill from 1806 showed he would order 50 bottles of Farina’s Eau de Cologne every month – which would equate to the average salary of 25 men!

Although I’m sure you don’t pay full price if you’re Napoleon. Someone probably cut him a “ruler of France discount”.

P.S

That’s not to say that Napoleon needed everyone to smell amazing. He famously told his wife “don’t bathe” when returning home from battle. Gross.

Healing Water

Throughout history, there was a sense that bad smells themselves were responsible for diseases.

The theory was that bad air made you sick. Which I guess isn’t too far from the modern theory of germs and viruses.

Close, but not quite.

People used to think that beautifying the fragrance of the air would ward off illnesses -instead of dealing with the underlying sanitary problem.

But confusingly enough, it would sometimes inadvertently work.

A great example of this phenomenon was during the Black Death – or bubonic plague. People would douse themselves in cologne and actually end up drinking it to boost immunity. Citrus oil would seep through their pores and emit a pleasant scent.

And it would somehow cause levels of plague in the area to drop.

“I smell great – the cologne is helping me stay healthy and ward off the plague” they thought.

Not quite. The citrus oil is a natural flea repellent, which was one of the main offenders transmitting the disease. It’s used in dog products to this day for the same reason.

This is one of many red herrings of history that would convince people of the mystical power of fragrance – but was just a case of misapplied science.

Eau de Cologne

We know that when Eau de Cologne began to dominate the fragrance landscape, it opened the door for imitators. Well, they were all in competition with each other, and had to find novel – and often underhand – ways to stand out.

Copycats would make outlandish claims about their colognes’ healing properties to stand out. Within a couple of years, many bottles would come with a note attached describing all the benefits a user could expect to receive.

Companies would claim all manner of ailments could be cured, from headaches to heart issues.

Eau de Cologne became so acclaimed for its healing properties that even doctors began to prescribe it. Apply to the affected area, inhale for 10 minutes – even drink it directly! This was all terrible advice.

There’s even a theory that such advice might have led to the downfall of Napoleon himself. In an attempt to boost his immunity, the Commander would eat what was known as “Farina ducks”, which were lumps of sugar that had been doused in Eau de Cologne.

That can’t be good for you. Napoleon eventually died from stomach cancer, and while ingesting cologne can’t be proven to be the cause, it certainly didn’t help much.

Perhaps he finally got that sense before he died. In 1810, Napoleon created the “secret remedies commission”. It demanded that perfumers be transparent with their recipes. This was so the potential medical benefits could be properly assessed and verified.

This was the beginning of the end for charlatan apothecaries and enshrined the separation of medicine and perfumery in law.

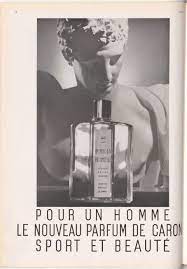

Modern Colognes- First Cologne for Men

Nowadays, we don’t associate the term “cologne” with Farina’s original creation. Instead, it’s used to refer to men’s perfumes as a whole.

But it wasn’t until relatively recently that colognes marketed to men specifically even existed. In 1934, Ernest Daltroff created “Pour Un Homme”, or “For A Man”. It was a calming and masculine blend of lavender and vanilla on a musky, cedar base.

Up until then, men only had traditionally unisex fragrances to choose from. In terms of masculine parfums, there wasn’t anything available except handkerchief scents and medical aftershaves.

As a result, Pour Un Homme was a huge commercial success. Suddenly, dozens of fragrance companies were rushing to develop men’s colognes. By 1938, the Shelton Company had released Old Spice, which is one of the most successful colognes for men to this day.

Sanitary standards had improved, leaving the medical qualities of aftershave largely obsolete. This caused many producers to shift their attention toward the fragrant qualities of their ointments.

With hundreds of new fragrances emerging, men’s fragrance had cemented itself as a niche in its own right. The public started using the term “cologne”, to distinguish them from “parfums”, or women’s “perfume”.

And the rest is history.

FAQs

When was cologne invented?

The original “cologne” was Eau de Cologne, formulated in 1709 by Giovanni Farina.

You can learn more in the opening section of this guide.

What was the first men’s cologne?

Caron’s Pour Un Home – or ”For a Man”. Ernest Daltroff was the nose behind the first cologne marketed specifically to men.

Pour Un Homme took the fragrance world by storm and opened the door for the cologne industry as we know it today.

Why is cologne called cologne?

Cologne is named after Eau de Cologne, which in turn was named after the town where it was produced. The fragrance used local herbs and fruits, so it made sense for Farina to pay homage to the location.

Now You’re Clued Up On the History of Colognes

If you’re keen to learn more about the origins of Gents’ style, check out more of our longer reads. There are some great stories by our expert writers, and we update them regularly.

More informative cologne reads:

Write a comment